December 4, 2020, TD Blog Interview with Sarah Mirk

Sarah Mirk is a Portland, Oregon based multimedia journalist whose work focuses on telling nuanced, human-focused stories. She is an editor at The Nib, the former editor of feminist magazine Bitch, and an adjunct professor in art and social practice at Portland State University. Ms. Mirk is the author of Guantanamo Voices: True Accounts from the World's Most Notorious Prison in which she conveys a number of first-hand accounts (including her own) in graphic form.

On December 4, 2020 I had the privilege of interviewing Ms. Mirk by e-mail exchange.

The Talking Dog: You are one of the younger people I have interviewed (in fact, on September 11th, I was actually older than you are now), and so I am particularly interested in hearing where you were on September 11, 2001, and what your experience of the last 19 years or so of living in the "post-9-11 world" has been like for you? Indeed, for your contemporaries, does September 11th itself seem even relevant?

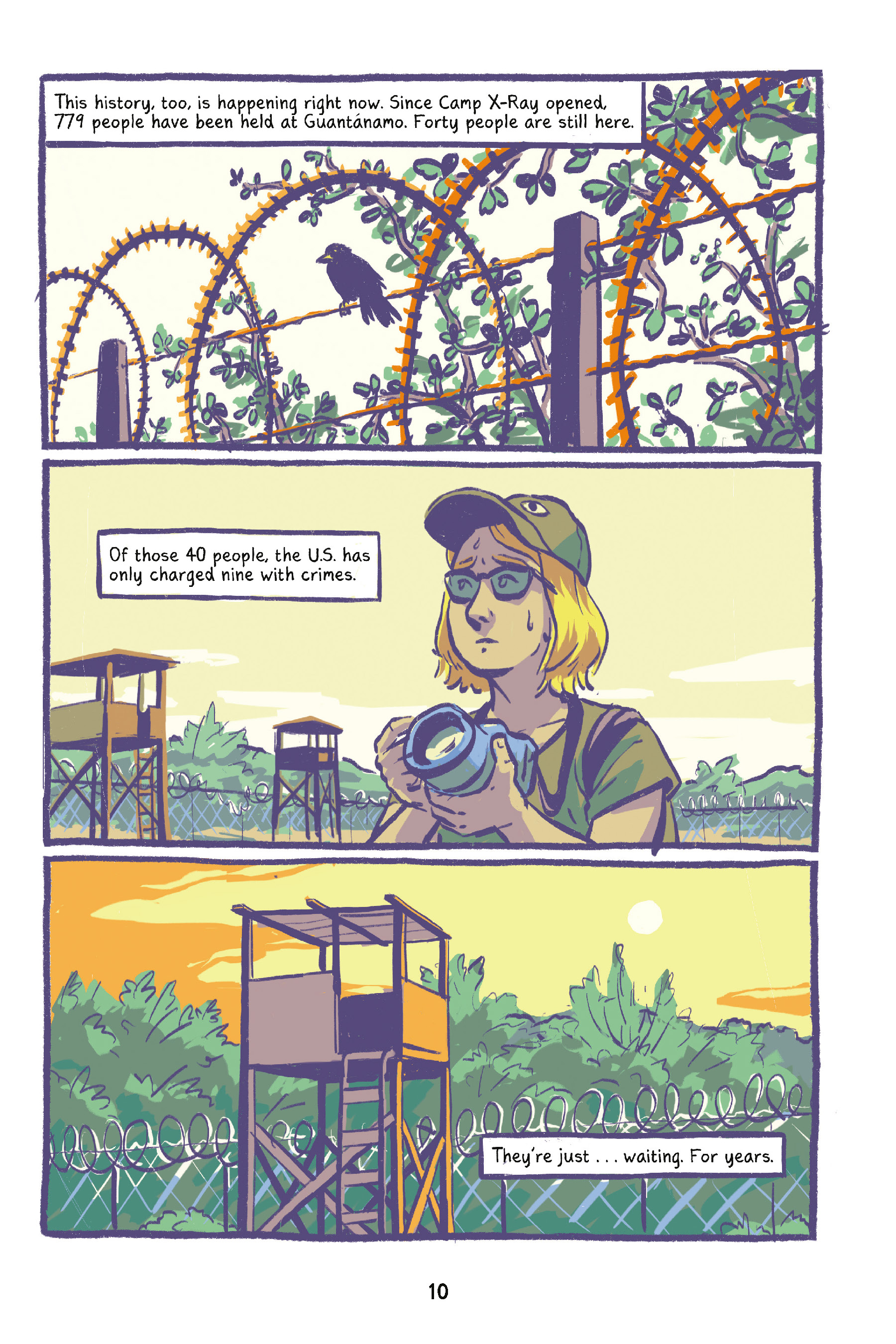

Sarah Mirk: On September 11th, I was a sophomore in high school. I remember hearing the news of the attack on the radio as my brother and I drove to school in the morning. I remember the swelling of patriotism and talk about hunting down terrorists—my neighbors had a sticker on their SUV that was Osama Bin Laden’s face with a target over it. I’m sure I must have heard about Guantanamo, but the news didn’t mean anything to me. “Guantanamo” was just a word I had in headlines and a single image, that photo of men in orange jumpsuits and black-out goggles kneeling in the dirt behind a fence. I didn’t think of it as a real place, full of real people.

September 11th definitely still feels relevant to me, in that it marked the beginning of a new era in so many ways. An era of war that seems like it will go on forever, an era of increased surveillance and lack of privacy protections, an era of intense Islamophobia. Of course, Islamophobia existed before, but attacks on people who were perceived to be Muslim spiked in the wake of the attacks and virulent bias against Muslims persists today. I think it’s really easy for all of these changes to fade into the background for people who are not most directly impacted by them. As a white, agnostic woman who’s a citizen of the United States, I’m much safer from the threat of state violence than many other people in our country. I’m not at risk for deportation, not likely to be surveilled by the FBI, not likely to face harassment or violence from police, I breeze through TSA. That’s a big part of why I felt it was my responsibility to write this book: This prison was opened in my name, to keep me “safe,” and I don’t fear retaliation from the government for reporting on Guantanamo.

The Talking Dog: Many people I have interviewed (especially attorneys for detainees) have lamented about the "image control" that the military has maintained out of Guantanamo-- that is, apparently, after receiving a negative reaction to the first pictures of men in orange jumpsuits kneeling in a barbwire enclosure, the military maintained absolute control of the photographic images coming out of Guantanamo (and indeed, later claimed complete control over artistic works generated by the detainees themselves)-- have helped the government's cause of demonizing the men held at Guantanamo and insulating the operation from more public outrage. Some of the images depicted in your book-- such as the force-feeding of hunger striker Emad Hassan, or the depictions of detainee "life" in the Mansoor Adayfi and Moazzam Begg chapters (or your own visit chapter), or the beating of Fouzi al-Odah or the tortures depicted in the Mark Fallon chapter-- are matters that the military "jealously guards" to put it politely. Prior to your depiction of "the Guantanamo story" in the graphic non-fiction genre, most images of Guantanamo consisted of court-room sketches of military commission proceedings (unsurprisingly reinforcing the "worst of the worst" narrative, as those images generally involve the alleged 9-11 plotters). People of "my generation" (at 58, I'm a year younger than my Columbia College classmate, Barack Obama) are arguably "more responsive" to photographic images than artistic renderings (let alone verbal descriptions). In the response you have received to your work (whether Guantanamo Voices or "the Nib" or other work), have you observed a "generational" difference in who "gets it," or is that a ridiculous question? How do you think this has worked out with respect to reaching a younger audience-- the "post 9-11" audience? Abu Zubaydah's drawings of the tortures he suffered are included in your book; as virtually everything he says is supposedly classified, do you have any idea how these drawings made it out of GTMO?

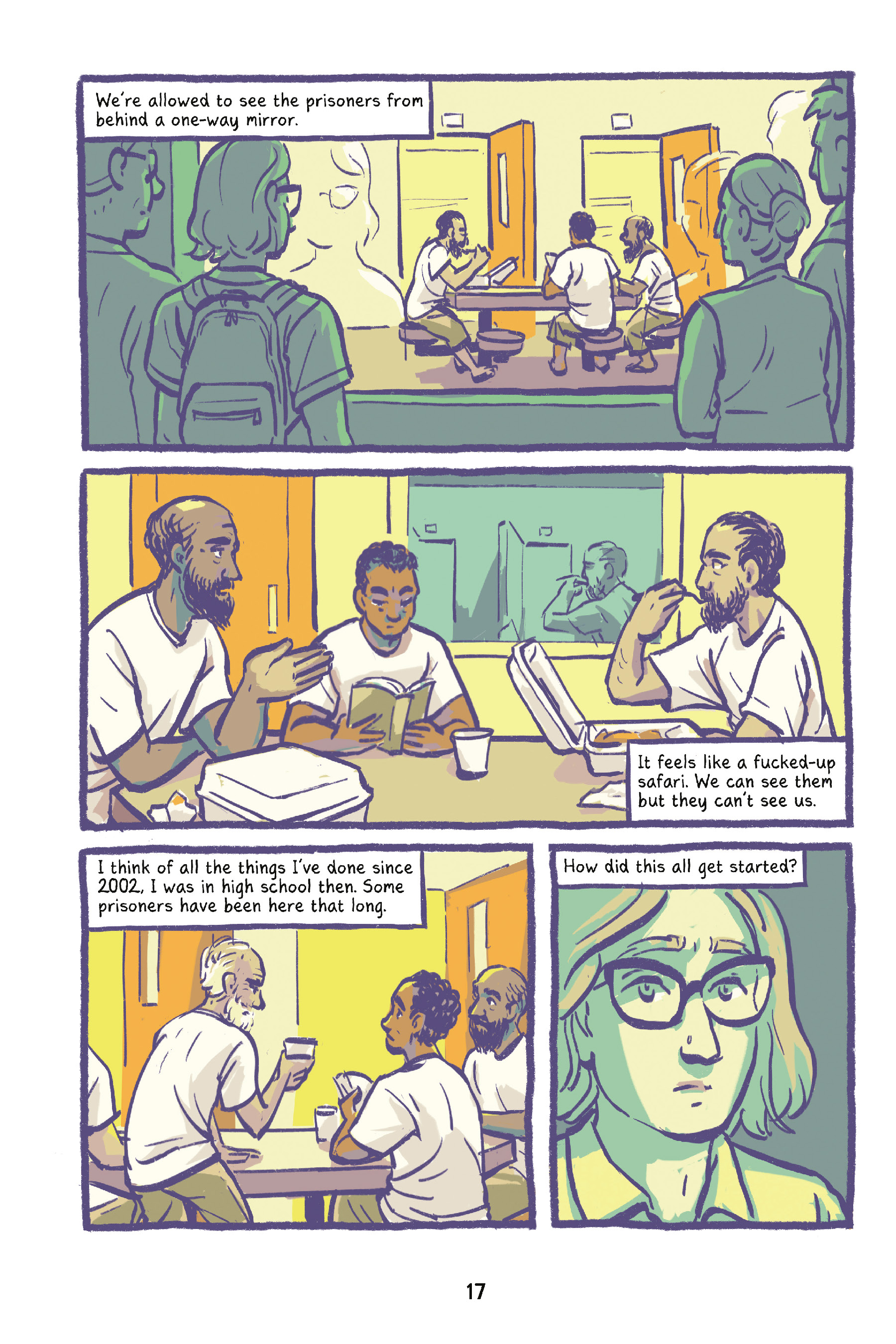

Sarah Mirk: You’re right that the government very tightly controls what we’re allowed to see of Guantanamo. This is part of the government’s overall strategy to control the narrative around the prison. The Bush administration told Americans that the prison was a place to detain and interrogate the most dangerous people in the world. Very early on, people who worked at the prison realized that wasn’t true—many detainees were picked up either by mistake or because people wanted the enormous cash bounties the U.S. offered for turning in suspected Al Qaeda members. But the government very effectively kept that under wraps and kept the prison out of sight, out of mind. Guantanamo was designed to be invisible, so any media that can help make the place visible is important.

In regards to whether there’s a generational difference in how people respond to graphic novels, I do find that there’s often a generational difference in whether people have been exposed to serious, nonfiction comics in the past. Many people of the Baby Boomer generation think of comics as either newspaper comics, like Peanuts, or raunchy, gritty underground comics, like R. Crumb or Trina Robbins, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and Diane Noomin’s work. But people my age and younger often grew up reading epic graphic novels like Bone and serious graphic nonfiction like Fun Home and Persepolis, so we’re more familiar with the dynamic storytelling of comics as a medium. I first read Maus by Art Spiegelman when I was in eighth grade. In high school, I was inspired by Joe Sacco’s comics journalism books and Lynda Barry’s engaging memoir comics. Both of those works made me aspire to document my own life and experiences in comics. Despite that generational difference in familiarity, I think that people regardless of age understand comics and feel their emotional impact, once they give the medium a chance. I know a lot of people my parents’ age who had never picked up a graphic novel until a few years ago, but get excited about reading more once they find a book or digital comic that resonates with them.

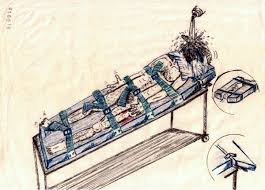

It was very important for me to include perspectives of prisoners in Guantanamo Voices. After reading about Abu Zubaydah’s horrific treatment in U.S. custody in the 2012 senate report, I was shocked and excited to see his drawings published in a New York Times article by Carol Rosenberg. I was shocked because the drawings are heartbreaking, it’s impossible to look at them without thinking of the physical, emotional, and spiritual pain that torture causes. I was excited because they are so expressive and I knew that they would have an impact on readers and help people understand the realities of torture. I’m not sure how the drawings were cleared for release by the censors at Guantanamo, but they were originally published in the journal article “How America Tortures.” I asked for permission from the journal article authors to include the drawings in the book.

The Talking Dog: We are (fingers crossed) soon coming up on the end of the Trump Administration. From my perspective, both because there are fewer men left at Guantanamo, other than in the military commissions, there is just less to talk about on the "legal" front, and Trump committed not to release anyone from Guantanamo. Other than Ahmed al-Darbi to Saudi Arabia, who completed a commissions sentence, Mr. Trump has kept that commitment (Trump has kept many of his more authoritarian campaign promises). I understand that your interest began at a chance encounter with former Guantanamo prison guard Chris Arendt, and you eventually followed Chris and former British detainees around the UK in early 2009 (coincidentally, I visited with Andy Worthington in London in the spring of 2009). You more or less stuck with this project for over ten years; what kept your own interest in Guantanamo up during this arguably "slow news quadrennial"?

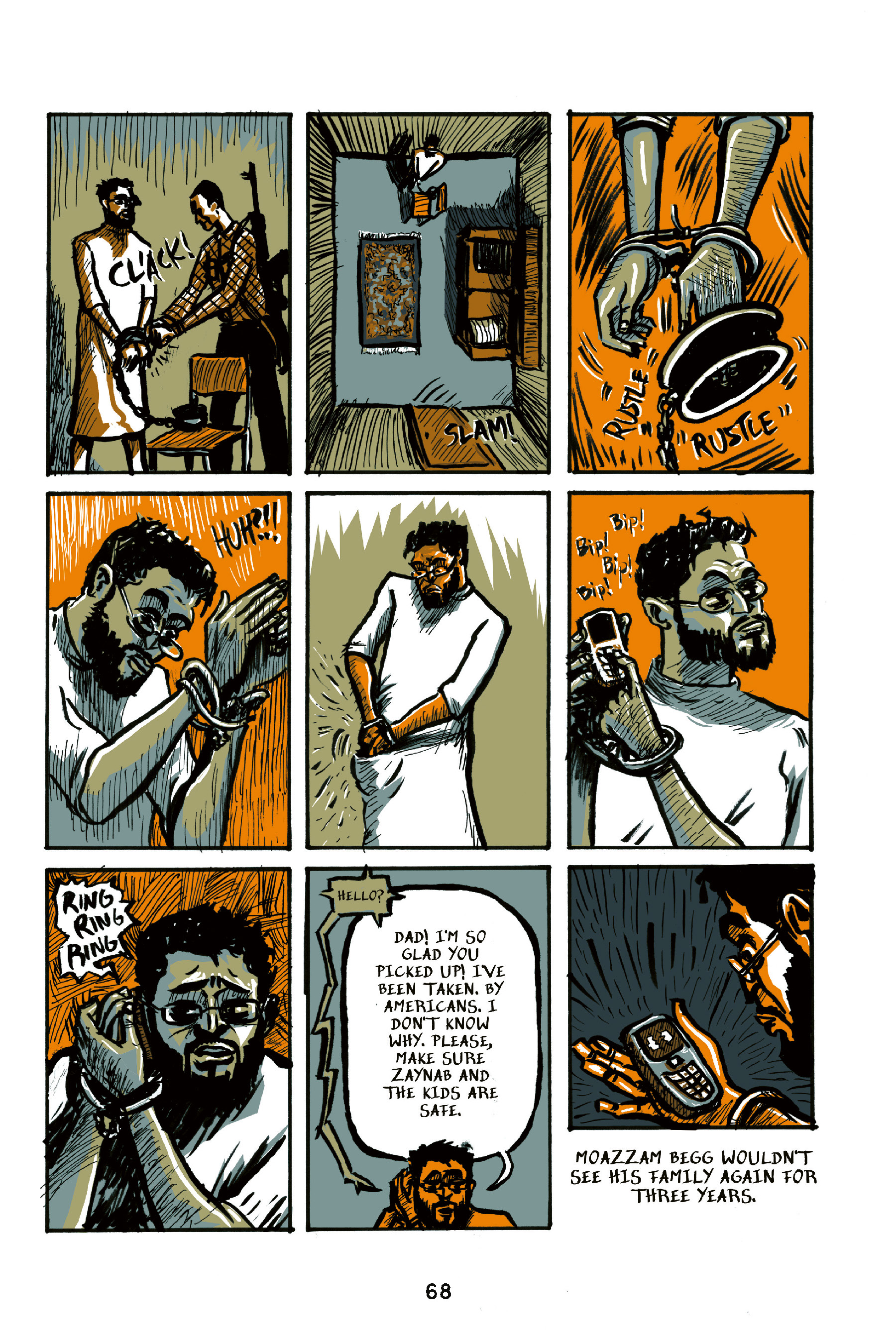

Sarah Mirk: After I met Chris Arendt in 2008 I wound up meeting a lot of people who had spent time at Guantanamo, including several former prisoners who work with the nonprofit CAGE, and many inspiring people who work as lawyers or journalists who try to seek justice and accountability. I got the chance to travel around England for a month documenting a speaking tour Chris and several former prisoners went on together in January 2009—I kept a blog of the trip called Guantanamo Voices. Their stories blew me away and I felt like everyone, especially every American, should know about them.

As soon as I got back home, I wanted to start working on a bigger media project about Guantanamo—I thought it would be effective to tell their stories in a graphic novel. But I didn’t know anything about how to write and publish a book. I was 22 at the time, working as an intern at a weekly newspaper, and had never met anyone who had written a book. Over the next ten years, I worked on my skills: drawing, writing, and nonfiction comics; writing several other books; managing a nonfiction comics project; getting an agent; and learning more about Guantanamo. All the while, Guantanamo weighed on me. I think it’s the biggest human rights abuse of our era. I know that in 20 years or 30 years or 40 years, we will look back and say, “How did we do this? Why wasn’t this abuse stopped?” I kept thinking that at some point, Americans would really start to take notice and care about Guantanamo, that people would demand en masse that the prison be closed and the people who approved torture prosecuted for their crimes. But over the years, instead, I just saw media cover Guantanamo less and less. It felt increasingly important to me to create a book that helps Americans understand the prison and face this terrible history, even though it’s hard.

The Talking Dog: How do you think your approach of trying to humanize the Guantanamo men and their situation via the text and images of graphic novels and comics has changed what you might call "the cultural narrative"? And in the age of Trump, is anyone listening (or do you sense something more bubbling up to the surface)?

Sarah Mirk I think the way to bring change to Guantanamo is to change the cultural narrative around the place and people who have been and continue to be imprisoned there. As we tragically saw during the Obama administration, without a demand from constituents, Congress will not push for justice and accountability—instead Republicans and conservative Democrats alike scored points by accusing Obama of trying to “bring terrorists to our backyards” when he aimed to close the prison and put some of the prisoners on trial in federal courts in the United States. So, Americans have been mislead about Guantanamo. The Bush administration dehumanized and stigmatized the people who were imprisoned there. Under Bush, Obama, and Trump, our values changed as Americans so that things that seem immoral are now seen as normal—for example, more Americans support the use of torture now than when Bush first took office.

But I personally believe that’s because Americans don’t understand the truth about Guantanamo and the people impacted there. We have seen Americans understanding evolve on a lot of issues, whether it’s racist police violence, sexual assault, or the impact of mass incarceration. I think Americans can evolve on Guantanamo, too. To do so, we need to center the voices of the people imprisoned in Guantanamo and the veterans who served there and know the reality of the place.

There’s never a good time to talk about Guantanamo. It’s not an upbeat subject and there’s no happy ending. So I don’t think people will go out of their way to learn about the prison and its brutal history. But I think it’s one of those parts of our country that we have to face. Like learning about the history of slavery, genocide, and other brutal injustices, it’s a reality we are better, as a people, for confronting honestly.

The Talking Dog: I assume you had some pre-conceived notion of Guantanamo-the-place. How did that compare with your actual experience of Guantanamo-the-place? How did it compare with descriptions provided to you by the people you interviewed? How did you manage to convey your actual GTMO experience to your artists (and I understand you had ten different artists for each of the ten chapters) in those cases where you were prohibited from taking photographs?

Sarah Mirk: When I set out to write this book, the first I did was read every other book about Guantanamo. I had a stack of about 15 books! The word that writers often use to describe Guantanamo is “surreal.” It’s weird to have a naval base that feels like a typical small American town, but on an island in the Caribbean. On the base is a high school, a grocery store, a library, a McDonalds. It’s weird to have regular life going on while just over the hill is the world’s most infamous prison. The other thing that journalists, lawyers, and former prisoners note is the ever-changing and arbitrary rules at the prison. Because the staff changes over frequently as people end their tours of duty, the policies are always in flux. What media can see, who we can talk to, what we can take photos of—all that changes frequently for no apparent reason.

So when I got to Guantanamo, I actually was not surprised at all. The rules on base about what we could photograph and not photograph was a nonsense comedy that reminded me of Waiting for Godot. First we had to submit all our photographs to be reviewed, then we had to submit them to a different person to be reviewed, then the word came down from on high that we couldn’t publish our photos at all! Why? No reason was given. It felt to me like the prison was a machine set in motion 18 years ago and no one has been in charge of it since then.

What felt different to me being at Guantanamo than reading about it was the experience of actually being in the place where torture and imprisonment took place. It felt like being on dark ground. I wasn’t sure how to act or feel about being on the actual site of such pain. I feel like Camp X-Ray should be turned into a memorial site, like the camps where Japanese Americans were held during World War II. But there’s no recognition of the brutality there. We’re a long ways from getting a memorial—instead Camp X-Ray is slated to be razed. I see that as such a concrete example of how we want to erase our past.

To convey that visual reality to the 12 artists who worked on the book, I took as many photos as possible of the places where I was allowed. I wanted to capture everyday life on the base, so I took photos of the base dining hall, the ferry, the Naval Exchange, everything. Then I put together a Dropbox full of those photos and hundreds of photos that were in other news reports or the public domain. I also shared both the scripts for each comic and the pencil draft of each comic with the people I interviewed, so they could weigh in as visual fact-checkers and correct any inaccuracies in details like uniforms.

The Talking Dog: Of the interviews in the book (Mark Fallon, Matthew Diaz, Moaazam Begg, Tom Wilner, Moe Davis, Mansoor Adayfi, Alka Pradhan, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis and Katie Taylor, plus your military escorts at GTMO) you present in text and picture, which ones (as many as you'd like) made the strongest impressions on you, and why (full disclosure, I know Shelby, and I've interviewed Mark, Moazzam, Tom and Moe)? How do you feel the presentation in the book held up with respect to that impression?

Sarah Mirk I deeply appreciate that each person in the book trusted me with their story. My biggest hope for his book is that the people I spoke with feel like I did their stories justice. One of the stories that has stuck with me the most is Matt Diaz’s. Matt was a Navy attorney who was assigned to Guantanamo. During his era there, the Bush Administration refused to tell the world who was even in Guantanamo—they would not release the names of the people in the prison. The Center for Constitutional Rights sued to get the names and a judge found that it was illegal for the government could not secretly imprison people without even sharing their names. But the Bush administration still kept maneuvering to keep the prisoners secret. Diaz found himself in a really difficult ethical spot. Because of his work on the base, he had access to a list of the prisoners’ names. He felt like his bosses were defying the Constitution… but if he protested, he could face a very steep price. He made the tough choice to engage in an act of civil disobedience: He printed off a list of the names and mailed them to a Center for Constitutional Rights lawyer. When he was found out, Diaz was sent to the brig and eventually disbarred. He struggled for a long time to find work.

The Talking Dog: You have observed that Guantanamo has leaked into our broader society, obviously in subtle ways, but even in obvious ways such as the Camp X-Ray cages looking eerily like the outdoor pens that Central American refugees, including children and separated families, were incarcerated in at the Southwestern U.S. border, or police covering their name-tags during recent protests that you covered in Portland. I have always thought of GTMO as a "demonstration project" (if nothing else, to get Americans used to the concept of arbitrary detention); do you have a particular view of the "gestalt" of Guantanamo into American life as we approach its 19th anniversary?

Sarah Mirk I think you’re spot on in calling Guantanamo a “demonstration project.” Guantanamo was a turning point. Once we failed to hold anyone accountable for what happened at Guantanamo, that opened the door to those despicable practices becoming more common. Guantanamo has normalized arbitrary imprisonment, as you mentioned, but also normalized imprisoning people for years without trial, dehumanizing Muslims, torturing people in U.S. custody, not allowing media access to prisons and prisoners, and having no accountability for political leaders who pushed for this indefinite imprisonment and torture. Instead, those political leaders have gotten book deals and been promoted. That’s really scary and sad. Altogether, this makes Guantanamo seem normal, instead of like an ongoing human rights abuse. Its continued existence undermines the rights that America supposedly aims to uphold, such as the right for everyone to not be imprisoned without charges.

I definitely saw a lot of parallels between Guantanamo and the treatment of Black Lives Matter protests this past summer. We’ve seen federal surveillance of protesters, mass arrests, and complete lack of accountability for police and federal agents who engage in brutality. When I saw local police and federal agents covering their badges in Portland this summer and also grabbing and arresting people apparently randomly off the street from unmarked vans, it definitely felt like a sad precedent set by Guantanamo.

The Talking Dog: We are now 12 years after the 2008 election in which Barack Obama famously promised to close Guantanamo, issued an executive order on his first full day in office to do exactly that, and then spent eight years dithering until he ultimately left an unclosed Guantanamo to Donald Trump (albeit with fewer prisoners, but even his government cleared 5 of the 41 men he handed off to Trump). As the Presidency shifts from one septuagenarian to another, how significant do you think that different means of depicting "the Guantanamo story" will be towards what activists hope will be the ultimate "closing of Guantanamo" as promised by Barack Obama 12 years ago by Joe Biden, the man who served as his vice-president? How optimistic are you that Mr. Biden will manage to do what two of his predecessors tried (and one didn't try) to accomplish, and close Guantanamo? What kind of public pressure do you think we will need to bring to bear on the incoming Biden administration?

Sarah Mirk I would say I’m cautiously optimistic that the Biden administration will close Guantanamo. It will definitely take a lot of public pressure, because as we saw during the Obama administration, Republican politicians in Congress will fight closing Guantanamo every step of the way. I think elected officials need to hear from their constituents that closing Guantanamo is important, so that people in Congress and the Democratic leadership feel like this is a human rights abuse that they can’t afford to ignore.

I also think we need to do much more than just close Guantanamo. We need to look backward to seek accountability for the leaders who built the infrastructure for torture and illegal imprisonment at Guantanamo and CIA black sites. This will be politically difficult, but we as a country need some kind of truth and reconciliation process to bring to light what happened at Guantanamo, hear the voices of the people whose lives we ruined, and take their guidance on what justice looks like here. The healing starts with closing Guantanamo, but it doesn't end there.

The closest historical parallel to Guantanamo is the incarceration of Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. Fred Korematsu, who famously fought a legal battle against his incarceration during WWII, actually signed a “friend of the court” brief in support of habeas corpus rights for Guantanamo prisoners. For decades after the camps closed, the United States did not reflect as a whole on that history. It took 40 years for the President to apologize and offer reparations. By the time I was going to elementary school, in the early ‘90s, the internment of Japanese Americans was in our textbooks and was framed as a grave mistake rooted in racism and xenophobia. I hope it doesn’t take us 40 years to start to reflect on the wrongs of Guantanamo.

The Talking Dog: How good a job do you see your colleagues in the media (of all kinds) in covering Guantanamo? Can you put that in the context of how public affairs in general are covered these days in a media environment ever more driven by sensationalism and infotainment?

Sarah Mirk There are a lot of really diligently reported articles and books about Guantanamo. I’m deeply indebted in my world to reporters like Carol Rosenberg, Charlie Savage, and Andy Worthington, who doggedly report on Guantanamo. But for whatever reason, many Americans don’t know what’s happening at Guantanamo or understanding the reality of what has happened there. I think it's very hard to get through to people with facts and numbers. Instead, humans respond strongly to personal stories. I think the book that has gotten through the most to Americans is Guantanamo Diary by former prisoner Mohamedou Slahi, because he shares his personal story.

That’s a big part of why I decided to build Guantanamo Voices about peoples’ personal experiences. I want to hit readers in the heart, to make them feel an emotional response to the atrocities of Guantanamo. I think this will have more of an impact to shape the cultural narrative around Guantanamo than trying to get through to readers just with facts and figures.

The Talking Dog: I join all my readers in thanking Sarah Mirk for that most interesting interview.

Readers interested in legal issues and related matters associated with the "war on terror" may also find talking dog blog interviews with former Guantanamo military commissions prosecutors Morris Davis and Darrel Vandeveld, with Guantanamo military commissions defense attorney Todd Pierce, with former Guantanamo combatant status review tribunal/"OARDEC" officer Stephen Abraham, with attorneys Pardiss Kebriaei, Nancy Hollander, Jon Eisenberg, David Marshall, Jan Kitchel, Eric Lewis, Cori Crider, Michael Mone, Matt O'Hara, Carlos Warner, Matthew Melewski, Stewart "Buz" Eisenberg, Patricia Bronte, Kristine Huskey, Ellen Lubell, Ramzi Kassem, George Clarke, Buz Eisenberg, Steven Wax, Wells Dixon, Rebecca Dick, Wesley Powell, Martha Rayner, Angela Campbell, Stephen Truitt and Charles Carpenter, Gaillard Hunt, Robert Rachlin, Tina Foster, Brent Mickum, Marc Falkoff H. Candace Gorman, Eric Freedman, Michael Ratner, Thomas Wilner, Jonathan Hafetz, Joshua Denbeaux, Rick Wilson,

Neal Katyal, Joshua Colangelo Bryan, Baher Azmy, and Joshua Dratel (representing Guantanamo detainees and others held in "the war on terror"), with attorneys Donna Newman and Andrew Patel (representing "unlawful combatant" Jose Padilila), with Dr. David Nicholl, who spearheaded an effort among international physicians protesting force-feeding of detainees at Guantanamo Bay, with physician and bioethicist Dr. Steven Miles on medical complicity in torture, with law professor and former Clinton Administration Ambassador-at-large for war crimes matters David Scheffer, with former Guantanamo detainees Moazzam Begg and Shafiq Rasul , with former Guantanamo Bay Chaplain James Yee, with former Guantanamo Army Arabic linguist Erik Saar, with former Guantanamo sergeant-of-the-guard Joseph Hickman, with former NCIS Officer Mark Fallon, with former Guantanamo military guard Terry Holdbrooks, Jr., with former military interrogator Matthew Alexander, with law professor and former Army J.A.G. officer Jeffrey Addicott, with law professor and Coast Guard officer Glenn Sulmasy, with author and geographer Trevor Paglen and with author and journalist Stephen Grey on the subject of the CIA's extraordinary rendition program, with journalist and author David Rose on Guantanamo, with journalist Michael Otterman on the subject of American torture and related issues, with author and historian Andy Worthington detailing the capture and provenance of all of the Guantanamo detainees, with law professor Peter Honigsberg on various aspects of detention policy in the war on terror, with Joanne Mariner of Human Rights Watch, with Almerindo Ojeda of the Guantanamo Testimonials Project, with Karen Greenberg, author of The LeastWorst Place: Guantanamo's First 100 Days, with Charles Gittings of the Project to Enforce the Geneva Conventions, Laurel Fletcher, author of "The Guantanamo Effect" documenting the experience of Guantanamo detainees after their release, with John Hickman, author of "Selling Guantanamo," critiquing the official narrative surrounding Guantanamo, with Rebecca Gordon, author of "The New Nuremberg" identifying potential war crimes prosecutions arising from the conduct of the War on Terror, with Naomi Paik, author of Rightlessness: Testimony and Redress in US Prison Camps since World War II, and with psychologist Jeffrey Kaye, author of "Cover Up at Guantanamo" concerning issues associated with detainee deaths attributed to suicide at Guantanamo, to be of interest.